Classically, Icarus is shown as a fallen angel, a muscled body in freefall. The focus is mostly on his flight. (Not his face.)

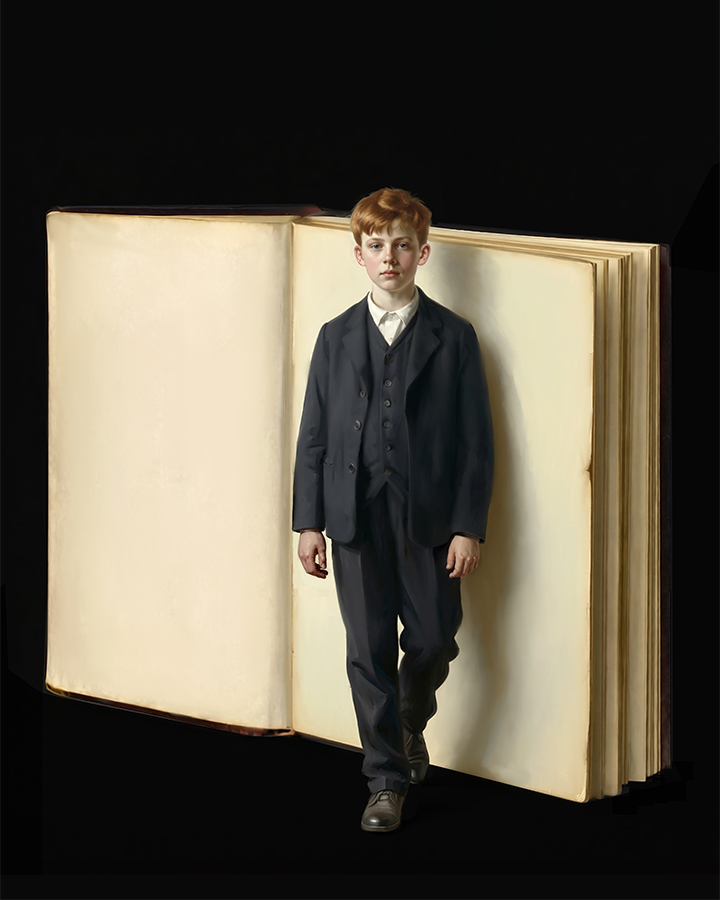

The paintings in this series imagine Icarus as human: at turns hopeful and penitent, ascendant and lost. My primary interest lies in experimenting with myth but also with memory, approaching the larger story as a series of shorter scenes, Icarus himself revived across a range of characters.

I imagine Icarus as a child, dreaming of adventure; Icarus as an adolescent, dreaming of escape. I think about the struggle with a demanding father, about the race to an unforgiving horizon line. I think about heat and flight but even more about terror and regret, and if I’m thinking about fathers, I’m thinking even more about feathers, weightless but mighty, ornamental and operational, both.

Pilot error. Wardrobe malfunction. Hubris, consequence, morality, mayhem. Ovid wrote about it all in the first century, describing Icarus as having a smiling countenance (“unaware,” he wrote, “of his danger to himself”) but what else was going on? If the sun melts your wings, what does it do to your skin and your hair? What does it do to your soul?

The story of Icarus is a myth and a fable, an allegory and a parable, but most of all, it is a cautionary tale. A boy buoyant. A parent defied. Who among us does not know someone flying too close to the sun? A cautionary tale always has a bigger story to tell. Icarus is all of us.